News

Barimar – Obituary 18/6/1925 – 20/11/2022

One of the last maestros from the golden era of the accordion joins his peers for a new venue in the sky

It is with great sadness that ZZ Music learned of the passing of Mario Barigazzi known to his fans the world over as Barimar. He leaves his wife and two daughters and several grandchildren. ZZ Music is proud to have organised a concert for a quartet dedicated to his music here in London back in 2018 where the group formed to perform his music played for the first time. What a pity Barimar himself wasn’t there to see it but well into his 90s he didn’t fancy the journey. We are also pleased to stock his sheet music on this site.

Romano Viazzani was very lucky to have collaborated with Barimar himself for one of the pieces in his London Tango album, a piece which Barimar had originally recorded as Mute Ande but insisted that Viazzani write an introduction to the piece that Viazzani had asked him for the sheet music of. The collaboration was renamed Barimar a Londra (Barimar in London). In 2014 Viazzani interviewed Barimar for Strumenti e Musica Magazine. Here is the link to Strumenti e Musica Magazine and the original interview in Italian.

For our English readers though we have the transcript in English here for your enjoyment:

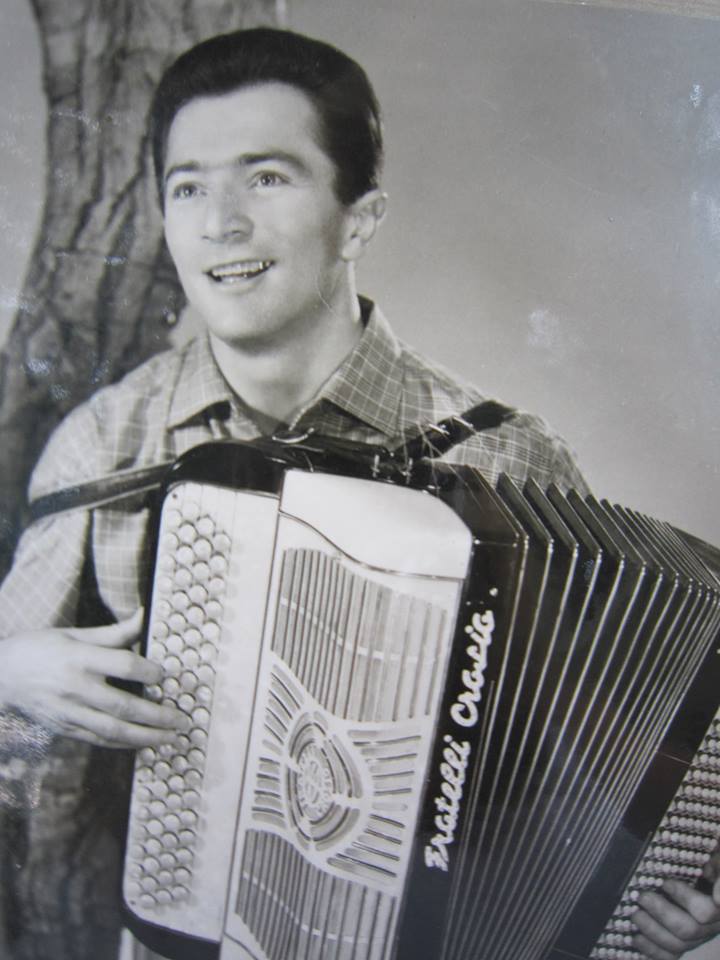

Barimar, born Mario Barigazzi in 1925 belongs to that group of accordionists who represent the Golden age of Italian Ballroom and popular Dance Music. That Golden era where the dance bands, of all sizes, from light orchestra to quartet featured accordionist-bandleaders whose names we all know. Gigi Stok, Nando Monica, Gorni Kramer, Wolmer Beltrami, Edoardo Lucchina, Iller Pattacini to name but a few. Barimar is nothing less than a living-legend. His recordings are found all over the world. Despite his years he still has the energy of a man half his age and his musical powers are undiminished. Regardless of his enormous talent he’s a very humble and warm man. Today so-called “Ballo-liscio” bands may well be good musicians but sadly their performances are rarely live, when they do play they play over a digital backing track, in some cases they may even just mime to a recording. Very few if any actually work in the way these bands used to in that Golden epoch where the leader would arrange the music for his ensemble. Every band therefore had a bespoke arrangement of the popular music of the day and each accordionist had his own identity, his own musical fingerprint which was unmistakable. But this is only part of his story. His name keeps cropping up in all kinds of recordings with many different formations, he has composed many accordion pieces and continues to compose and record many of his new and very original solo accordion pieces.

RV: Barimar. It is a magical name that represents a golden age and for me personally a name that has greatly influenced my musical education. In fact I would say that you were the accordionist who made me realize that the accordion did not always necessarily have to dominate the melody with the typical sound of the accordion. Sometimes, in fact, with a 16 foot reed in cassotto, it could hide among the winds in an equally important role as part of a section. It could imitate other instruments if it was played with the same imagination that you had when you played. Our readers need only hear your arrangement of Fascination to hear how the accordion can play the role of a second or third saxophone, or the latter part of Rosamunda (Roll out the barrel) where an accordion takes on the roles of clarinet and trombone in a truly Dixieland-style finale section. When I had my own dance band in London between 1981 to 2002 I must confess that I too used these techniques of orchestration to expand my line-up of nine nine musicians in order to reproduce Big Band arrangements by Glenn Miller, Artie Shaw and so on. Where did these orchestration ideas come from?

B: You may have noticed in these recordings that so many things are improvised. We try to do the best to orchestrate with dignity, to do nice things. Some are successful, others less so.

RV: It seems to me that in those pieces you managed very well indeed.

B: Yes. Then there is always the problem, as was the case in the record series Permette un ballo (Edizioni Ricordi) that I would be asked to take into account the fact that this was a piece of dance music and the dancers prefer a simple melodic line. This demand clearly held me back a bit, although sometimes I could have a little fun, as I did in the piece “L’Indiavolata.” However, the series went very well because we made 25 different albums!

RV: I have a wonderful book called Tutti in Pista(Boccacci- Edizioni Azzali) where each chapter talks about the different orchestras the Emilia region starting from Augusto Migliavacca’s string trio, the Cantoni wind band, the “dopolavoro” after-work bands. Among the great dance bands in that book were two photos that are impressed in my memory. One was a large light orchestra in the thirties with strings, woodwinds and brass with Nando Monica sat, accordion on his lap, amidst all these musicians; and the other, a beautiful photo of the 40s of an orchestra with about a 20 or so musicians including brass, strings and brass, plus singers and in front of the orchestra, its leader, Barimar standing behind his accordion, with his name in neon illuminated on the back curtain. What do you remember of that time, and are there recordings of that orchestra?

B: No. There were things done for the radio. So I do not know if the time they were recorded. However, I’ll tell you one thing. In Milan they opened a venue similar to the Moulin Rouge in Paris, I think called the Olimpia. There was a stage for jazz musicians, Chet Baker Quartet played there too various quartets and so forth. The restaurant was opened by Gorni Kramer and I also played there with that large ensemble. After two or three years, however, it closed, because – you know – Milan is not Paris …It went awry but I remember very well that at the same time I had a contract with EIAR (which later became RAI) and there were broadcasts at six in the evening, and we took the instruments from the Olimpia and we went to Corso Sempione, where we did the live transmission and then back again for a half past nine start at this place. I do not remember if it was called Olimpia or otherwise.

RV: Was it a grand hotel …or a theatre?

B: It was a venue with three areas. There was the dance band, the jazz corner, and a section dedicated to light entertainment. This was the period of the photo you mentioned.

RV: That was Nineteen forty …?

B: I was twenty or twenty-two, so we’re talking round about 1947… just after the war. Basically that’s when I started. And another thing. I had a trio at EIAR (RAI) with myself, Sangiorgi, the pianist, and Cosimo Di Ceglie. It was just Cosimo Di Ceglie who introduced me to Jazz. He was the number one guitarist at the time and then there’s no turning back to the days when I had started out with the theatre company. There were also Bixio and Cherubini, the top songwriters of the era … and…maybe I should start from the very beginning, if I may.

RV: Absolutely.

B: I lived in Carignano, 10km from Parma – there was a boy who would pass through Carignano, my home town, by bike, on his way to Felino for his accordion lessons complete with accordion on the luggage rack. One day my father wanted him to stop.

“Play me something.” And the boy answered him, in dialect,

“It’s only been three or four months since I started and I’m not good enough yet.”

“Just play whatever you like.”

“I watched him carefully and noticed he was playing the bass in one way and the right-hand keys in another way, and it made an impression on me. So I started to take lessons and with many sacrifices on my father’s part, because it was not easy to afford to spend the money to buy an accordion. My father used to rent some land which he worked, and sometimes I wanted to go help him and he would say to me, “You go home and study and don’t worry about the rest”. I’ll never forget this because he was so keen for me to play, and wished that I could play, perhaps maybe even if only for the village fete, he probably did not think about things beyond that. Then it happened that Tienno Pattacini – you know…the composer of Battagliero?…

RV: Of course.

…Well, Renato Benelli, who was the accordionist in his orchestra, had go to do his national service and so was looking for a replacement. Many players auditioned, I do not know how I got to hear about it. My brother played the trumpet and was five years older than me said to me,

“I’ll take you to Barco.”

From Carignano in Barco meant 25 km by bike! So we took the instrument, went there and played for Tienno Pattacini. He chose me among all those who he had heard, and I accepted the post. But he didn’t play for dancing. It was a show … In ’38, ’39 I was thirteen or fourteen. It worked like this: at the end of the show at night, I took my bike, I left and went all the way home to sleep. Thinking about it now, it makes me shiver. The risks I took cycling when it was pitch black and the only thing on the roads were barking dogs! I was happy to play but then I wanted to go home. I’ve always been stubborn! Tienno’s mother, who loved me dearly, would say,

“No, stay here.” But I wanted to go home. I have to thank my father for the sacrifices he made and Tienno Pattacini because he set me on the right path. It also made me realize that it wasn’t enough to just play well and that to become a professional I needed to study harmony and counterpoint. So I went to Maestro Pietro Tamani in Parma.

RV: He had an orchestra too, right?

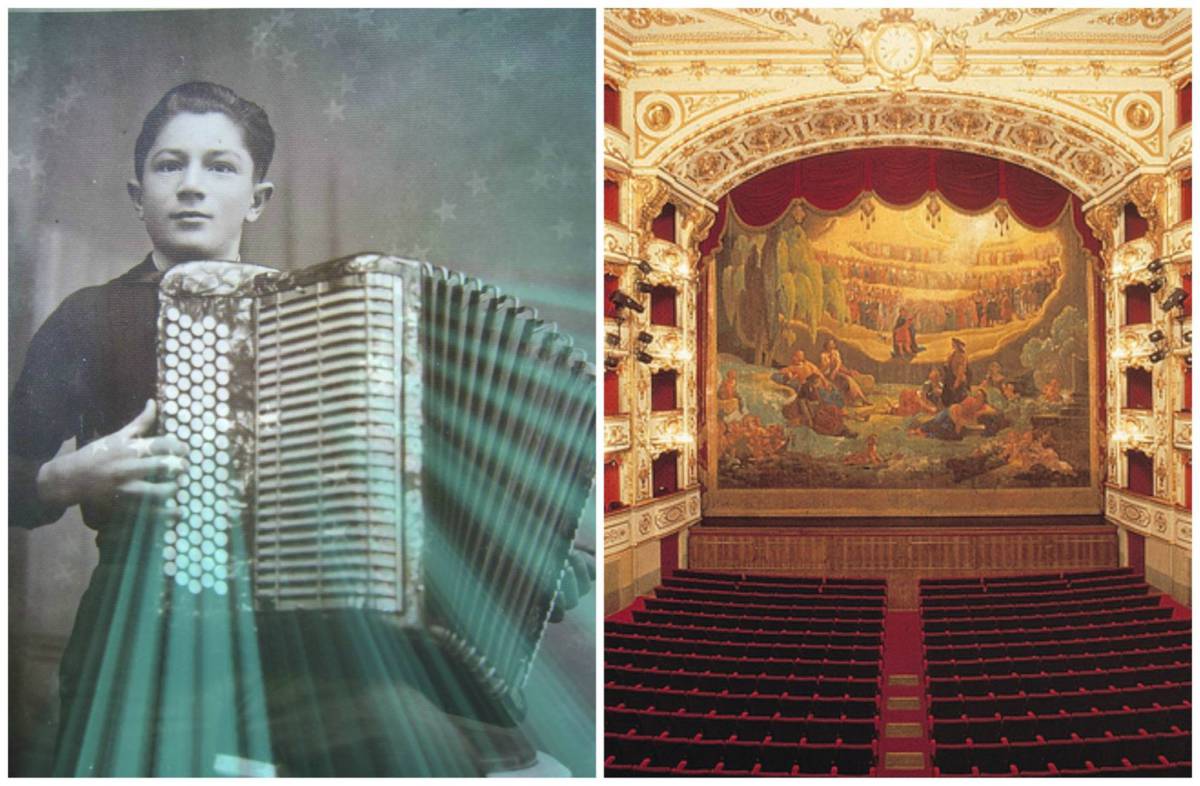

B:He had an orchestra, he was a pianist and I studied there and later in Milan at the Scuola Civica in Corso Venezia. But I couldn’t study exclusively, I also had to earn my keep so I also started doing gigs. When I was studying to Tamani I was staying with my Uncle in Parma. One day I spotted in the paper that there was to be a show at the Teatro Ducale called Autori alla ribalta [Composers to the fore]. So I went to the theatre and suddenly I heard the announcer say,

“We have been made aware that there is a certain Mario Barigazzi in the room.”

I thought they were calling me to tell me something terrible had happened. I was worried …

“Come up on stage”, they tell me. I was right in the front row. I go up on stage, shaking, I’ve always been shy. They ask me,

“You play the accordion, don’t you?”

“Yes,” I replied.

“Will you please play something for us because we know that you are very good.” He said.

“Oh, I would love to do but I have not the accordion with me!”

“But we’ve got one!” came the reply.

They teased me by carrying a piano accordion on to the stage and I did not know how to play that one, and then they brought me my very own accordion. And so there I had to play. But you know what had happened? At that time I was playing with with Emilio Ferrari, son of Italo Ferrari, the puppeteer – he was a professor of violin. We had formed a quartet in Parma in a room in Piazza Garibaldi and he had heard of these shows and said,

“I want Mario to be heard by this theatre group.”

So he went to my uncle to ask for me. My uncle replied that I had just gone to see a show. Then he had to decide between the two theatres. The closest was the Ducale Theatre so he deduced that I would be there. He picked up my accordion and took it to the Ducale. So I had to play! I did three or four pieces. Luckily, by chance I was prepared and well-rehearsed and everything went fine. In those days we would play The Carnival of Venice by Frosini, then the Moto Perpetuo by Paganini, but that night I played La Gazza Ladra (The thieveing Magpie) which was rather unusual for the times, in the sense that they were used to another type of repertoire.

Well, the manager said to me,

“Prepare yourself because at most, in a month’s time I’ll send for you and I want you to be part of our company.”

After a month his secretary came to Carignago where I lived and my father asked him who he was “What do you want with my son? My son is not here. ”

“Where is he? The manager and the chief comic want me to take him to Milan. ”

He stayed quite a while and spoke in Milanese dialect to sound more local. In the end, he told him where I was. I was in a village 15-20 km below Parma with another uncle. In short, he finds me and asks me to go with him, but I had a fever and I told him that I could not leave.

“You have to come with me now or never,” he told me.

So in spite of everything we departed by train, and arrived in Lodi where we joined the theatre company. After the show we all went to eat at the restaurant and by the end I could not wait to get to my bed. I was ready to drop. And they carried on chatting, you know. Finally they brought us to the hotel. One here, one there, and as I enter the room I am met with Valdemar, a very good comedian from Livorno … a hunchback, who started to jump from one bed to another and I wondered what on earth was going on. Eventually I realised it was a joke because they others were all at the door laughing like crazy! Finally I had my room!

Then, also with them at the time, Bixio, who wrote Mamma, said that Mario Barigazzi, as a name didn’t really fit and that we should find something different. And so we settled on ‘Barimar’, an acronym between Mario and Barigazzi.

RV: Wonderful story. We talked before the big orchestras. I assume that the amount of musicians was necessary, not only for the sophisticated sound of the era but perhaps because there was less amplification around at that time. Was it perhaps the development of improved amplification systems which reduced the numbers of musicians in orchestras or were there other reasons maybe, perhaps economic reasons?

B: Other reasons for sure. The cost mostly, because I remember that I had many formations. Before the large one in Milan we mentioned before, I had formed a sextet. We went to play at the seaside for example, a month here a month there, then, I can barely remember some because every time situations changed, so did the orchestras. I cannot forget those fifteen years at La Voce Del Padrone (His Master’s Voice) as conductor and arranger with the singers of the time. It was Jula de Palma, Luciano Virgili, Narciso Parigi …They were 15 years when I was truly blessed in the sense that yes, I was free to go and work for a month at seaside with the ensemble, but the important job with them remained.

RV: Which years are we talking about now?

B: From ’55 onwards. The first thing I wanted to say is that, once I started at La Voce del Padrone, we were four or five conductors, and the work we were doing was scrutinised by the parent company in London; His Master’s Voice. I’m speaking now of the early days of television. At the very beginning of television I did two things: I participated in a television link playing classical pieces for accordion for solo accordion in a studio in Milan, whilst being recorded in Turin; The other interesting thing was the union of two orchestras, and The Columbia and His Master’s Voice, who doubled the 20 musicians to 40. So, arrangements with 8 trumpets, 10 saxophones? What do we do? Play in unison? Then I thought we could try 4 open trumpets without mutes trumpets and 4 muted, in fact I wrote a piece especially for this broadcast.

RV: Was the accordion in that particular orchestral formation?

B: No. When I played with the singers at times, I would intervene on accordion as did Kramer, for example with a simple phrasing rather than with a solo piece.

RV: At that time there was rivalry between dance bands and there were always good relationships among them? I ask because I see a lot of collaborations in the compositions for accordion between accordionists but perhaps they were written in a more recent era.

B: I have had little contact with other accordionists. Except with Stok. I must say that with Gigi were like brothers, not colleagues. We admired each other, we exchanged compliments. For example, when I let him hear Gipsy, I do not know if you knew Stok and how he was …

RV: Yes. I did meet him.

B: He started to jump because he loved it. The rivalry did not exist. Back then I had done things with Wolmer and Kramer for the radio. There was no rivalry there either. In addition I was younger than them, and as you’ll understand, I was already an admirer of Kramer and Wolmer, but to find myself playing with them was a great thrill.

RV: Something similar happened in England a few years ago with Jack Emblow, the renowned English jazz accordionist, now in his eighties, too, who played for the first time with Art Van Damme, who Emblow greatly admired, and a jazz quartet at a festival in Caister, England, perhaps it was the year before Van Damme died,

B: I admired him too!

RV: Emblow playing with his idol, was visibly moved by the experience. For us, who were listening intently it was a magical moment.

B: He really was very good. You know, it’s funny, I always turned down the invitation to make an imprint of my hand at the Accordion Museum of Recoaro Spa. One evening I went to do a gig with Stok. There were three days of Italian accordionists all there to do a little playing, here and there. “Come with us to Recoaro and put your handprint,” he would say and I would reply “No, I don’t’ really want to,” Anyway, I managed to avoid going. But, then I succumbed when I found out Art Van Damme was going to be there!

RV: It’s nice museum. Small but nice. I have been there too. In fact, on the internet I saw one of your performances that must have been recorded there in the theatre. If I remember correctly you are playing Autumn Leaves.

B: Yes, I played in Recoaro many pieces and someone made a video while doing Autumn Leaves. I saw it too almost by accident. I did not want to play but Gigi Stok said,

“Pick up the accordion, you never know.”

Finally, I saw the theatre, and that you could play without a microphone and it made me want to play. So I picked up the accordion and played. It just so happened that someone recorded it.

RV: For today’s internet-savvy generation, it’s a good thing that such recordings exists because it’s a way of hearing a live performance by musicians of your generation.

B: On the internet there are some videos, especially on my Facebook page. Something I did for RAI TV in the 90s.

RV: Apart from the many recordings you made were there many broadcasts on radio or even television?

B: Yes, as I said before, I recorded the programme Funari “Mezzogiorno è…” RAI-2, and there are some videos from it on Youtube. [Links]

RV: I collect records on the internet and when I do a search on the name Barimar I see recordings from all over of the world with different ensembles, as well as the collection from the Permette un Ballo. A number of titles related to San Remo for instance, another group called The Barimars, Barimar and Capricorn College (Prog Rock), the list never ends! I do not know if another accordion player of your generation has had an experience that is quite so vast. Could you talk a bit about these various groups?

B: Yes, I certainly had a great experience. The content and value of some of the things I did done may be debateable. For San Remo, for example, they gave us the songs to record a week before and they had to be ready in a hurry. So in the arrangements you really could only put a few chords here and there as there was no time. It was not a pleasurable thing. I did it for many years back in the days of Nunzio Filogamo.

RV: That would have been in the 50s or 60s?

B: Well, yes, in those years again. The time when I was at La Voce Del Padrone.

RV: And I Barimars? Was that a different formation?

Yes, it was another formation. I was no longer in “La Voce Del Padrone.” [His Master’s Voice] I was with another record company. The first disc we did as Capricorn College which was a progressive rock group. It was recorded to fulfil the demands of the day. So you were trying to make ends meet … we do a bit of this, a bit of that. It was a name I could use other situations, such as playing in night clubs.

RV: Yes, in the sixties the accordion had gone out of fashion. I know Gigi Stok began playing electric bass at that time. I also know that many couldn’t wait for him to pick up the accordion to play a couple of waltzes. How did you cope with this new trend? Did you continue to play the accordion or did you have to adapt?

B: With the accordion I stopped. I had the vibraphone and the Hammond organ. I’m not really an organist but those pieces were not difficult. I had to adapt. You know, when you’re in Milan, family, profession and …it is still my job.

RV: This happened in England too. From ’63, ’64 onwards no one wanted to hear the accordion. Armando Guselli, a fellow accordionist who I played with for many years in the UK, also took up the Hammond organ, Corrado Medioli, in Italy, played the bass and the vibraphone.

B: We made do. But I had musicians who did this kind of music very well and the record we made as Capricorn College was not commissioned by anyone. Then I finally presented the recordings to Ricordi in Galleria del Corso in Milan and they accepted it for distribution. They were excited and they published it under the name Kansas. It was the period of the New Trolls, ABBA and lead us into that world, but it was not easy.

RV: It’s very nice. It’s there on the internet.

B: It is sought after by collectors. Many ask me but I do not have any more copies!I had one, but a fan from Bari called me with such enthusiasm that I sent him my last copy.

RV: In the seventies, I remember, however, that there was a revival of so-called ” ballo liscio” (Ballroom dancing). I re-emerged a little more folky perhaps than before, and a little more linked to the Romagna region perhaps due to the popularity of the Orchestra Casadei and others. I have a theory and maybe I’m wrong. But the term “Liscio”(literally “smooth”) was coined after the sixties possibly to distinguish between dancing as a couple “smoothly” and dancing alone to the dances of the day (shaking, twisting etc), ie without physical contact, or did the term exist before?

B: I don’t think this term did. I wasn’t a great lover of “liscio”. We did the traditional ballroom with a four or five piece ensemble. We played swing and pieces of the time.

RV: It was known as dance music? It wasn’t known as “liscio” before.

B: I’m not sure exactly how did the term “liscio” came to be. I never tolerated it. I would have liked to have played what young classical accordionists study today, but it was not possible then. When you have a regular job you do what you can. You say to yourself, I’ve will affirm myself as an accordionist. I also set shows to music, and where are the shows now? They ended years ago.So many things started and then finished. I owe a lot to Tienno Pattacini, because it gave me a bit of impetus to expand my musical knowledge. I know that you wrote your own Concerto for Accordion and Orchestra …

RV: Oh! Did you like it?

B: I liked it, I liked it, I envy you a bit. Bravissimo. And then there’s also your Gigi Stok Fantasia for accordions and symphony orchestra. Too bad he is not here to hear it …

RV: We had invited him to London for the London Accordion Festival in 2001 but he was already ill.

B: A very sad end, yes. He did not know where his house was in the end. He would go out cycling occasionally and could no longer find his way back.

RV: Another one that I met briefly at Parma was Bruno Clair, aka Bruno Stocchi, cousin to Gigi Stok, but it was already in poor health.

B: He was the cousin of Gigi. I’ve never heard him play. I do not know how he played. I think he preferred not to adapt to play a bit ‘of everything. I do not know how it went for him.

RV: You will have known Umberto Allodi’s brother Bruno who was selling accordions in London, an business that continues today through his son Emilio, and his other son Claudio plays accordion for a living.

B: Of course. As a boy I was very impressed because he played the Moto Perpetuo very well.

RV; Umberto was playing an accordion with free bass even at that time. He had an accordion with nine rows of bass buttons, that is, the system that is known as the “Modena” system, a bit similar to a Stradella Standard bass turned upside down and arranged in straight rows, plus three rows of free bass.

B: Yes, in fact. I do not know how I managed to win the competition of ’46. Bruno Allodi also participated. When I saw him I thought it had no chance. Instead I did.

RV: I see from the CD you gave me the last time we saw also that you continue to compose pieces for accordion. I was genuinely surprised at the originality of recent pieces that you have composed for accordion solo. They are pieces that should be published and played in competitions for accordion with standard bass. They have a freshness that is undoubtedly a vast experience. What else have you composed that perhaps the public do not know about?

B: You know that after this chat we had if I my legs were still able to I would jump for joy! (They laugh.)

RV: I’m talking about pieces like Profondo Buio. I was surprised because I had heard your recordings of music in the popular vein, but …

B: I would have wanted to do things like that, both as a performer and as a composer. These things I have written without thinking about proposing them to someone in particular. I needed externalise a little maybe when I got back at five in the morning after playing at the nightclub. Those songs were born in Milan, forty years ago. I wrote them for myself and then I showed them to Capitan Editions, a publisher of Reggio Emilia, who published them.

RV: They seemed even more recent and they are beautiful.

B: I’ll have fifty of those things. I write all the time.

RV: So many times in competitions when I’m on the jury, I hear the same pieces played by competitor after competitor, every teacher has a repertoire he or she teaches students. Not only are the same pieces repeated but also often the way they are played is the same too. Fortunately, every now and then comes a composer who offers something new, as has happened in recent years such as teachers like Renzo Ruggieri in the light music categories and composers like Franck Angelis in the in the contemporary music categories who keep the repertoire fresh. I like your pieces a lot.

B: Coming from you I should be very happy.

RV: I hope they will be discovered soon and that someone plays them in some competitions because I’m sure no one has ever played these pieces. They are musically profound, not just technical, although I would add that they are certainly not easy.

B: There was a desire to express something without anyone having commissioned anything from me. It was a need. For example, Profondo Buio [Deepest Darkness] is a piece that I was inspired to write by the situation of a person close to me who has had many problems, life problems, including depression and when someone tells you about something so dramatic, that you yourself may never have experienced, it leaves one feeling chilled to the bone. I was very affected by this and wrote Profondo Buio. Whether it’s successful or not, we should not be the ones to judge.

Like Sul Treno [On The Train]. It was an appealing piece because I was just on the train to Florence and I did not know what to play and at the end I wrote that.

RV: Who was your accordion teacher?

B: My first teacher was Marmiroli. You know, little waltzes and things like that. Then I started to listen to records by Wolmer and Kramer. And definitely studying is very important, but also knowing how to listen is too, and especially to classical music. And then everyone has to leave their mark in some way.

RV: Were there competitions for accordion in those years? The competition that you won was in ’46 you said?

B: It was the national competition in Stradella. Marcosignori, who was younger than me, was there too in the beginners section.

RV: Readers of Strumenti e Musica are always interested in the system of accordion played by the various accordionists who we interview. You play the C Griff button keyboard in your right hand but in your left hand, however, a system that today is becoming quite rare; the Modenese system. How did you come to have this system?

B: I was given a wooden accordion with only three rows of buttons with that system. It had 46 basses.

RV: We talked about the inspiration that you have given to other accordionists like me. What are your musical influences? Who gave you inspiration in the accordion world and then in the world of music more generally?

B: It was initially Paganini. If you take my Sogno del Prigionero [The Prisoner’s Dream] there are technical references to Paganini. Then, let me think … Menuhin. I always aim high eh?! I think we definitely need to train students both technically and also by listening to classical music for phrasing.

RV: You have pretty much answered my next question is, what advice would you give young accordionists today who want to be professionals of tomorrow?

B: Definitely to study by themselves too, is the first thing. All professions are difficult. Whoever wants to do this job today needs to have a great talent, that not everybody has but if it is there then it’s a good thing to be able to cultivate it. In any case, the music is something that accompanies us all our lives, I say this from experience because for me it is still important to be able to play and still make recordings.

RV: What do you think of “ballo liscio” today? Has it future?

B: “Liscio” is a genre that was highly sought after and one that I have played too, as well as others. The fact is that before the “liscio” boom I had a group that played in nightclubs. One night a guy sent for me during the break and said to me, “Look, we’ve had the Casadei Orchestra two nights in Milan and was a big hit.” I asked him, “What kind of music are they doing?” He says, “They do waltzes, polkas, mazurkas, in short, people really liked it. Would you come with your orchestra? We would like to open a venue … “I was amazed and I agreed to meet him. We met, a restaurant was soon opened, after which another two followed and I started to adapt to that kind of repertoire which was not exclusively traditional because we had to music like even Blue Moon for instance, some ‘swing and other dance music. In short, it worked, up to the point that they opened another establishment which also had a great success. I thanked God because it was a difficult time. One had to move continuously, whereas there, we played a whole month in the three venues alternately. The whole thing continued for two or three years. Fortunately, even though I couldn’t take it anymore, even if in the end we made good money. We had a repertoire of 500-600 pieces. Then I left the ensemble to establish another with two guys on bass and guitar, who very good. It was called Historia Barimar and we decided the programme together playing very contemporary, modern music.

RV: I was so grateful to be able to interview an accordionist who has inspired me so much as a young accordionist and I only regret not having had the opportunity to interview other accordion players of your generation. A generation which should to be remembered, one of great musicians with wonderful imagination, good taste, and a good musical education, from a time when the so-called “liscio” was really beautifully played live, even though “liscio” is only part of the story of this genius called Barimar. A big thank you from me and from all of our readers for giving us this interview.