News

Toralf Tollefsen – World Artist – Book reviewed by Michael Lieber

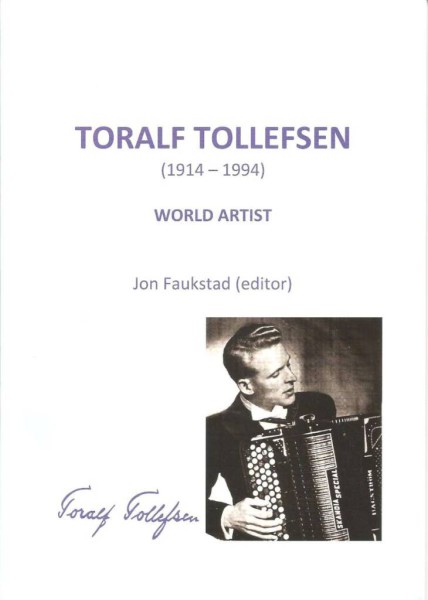

Toralf Tollefsen (1914-1994): World Artist

Edited by Jon Faukstad, translated by Owen Murray

Toralf Tollefsen was to Europe in the 20th century what Charles Magnante was to the United States, consummate musicians who did with the accordion what no one else had. This book is a narrative of Tollefsen’s life in his own words, transcribed from interview responses to his colleague and editor, Jon Faukstad.

Tollefsen describes learning music in his family from his father, siblings, and uncles. He began lessons and playing in a group in his early teens in Oslo, where he played in a restaurant, at local events, and began recording. He describes moving to London, where he quickly became a fixture and a feature artist in variety shows performed live, on the radio, and on recordings. It was in a variety show where he met the woman who became his wife. He and his wife returned to Norway just before it was occupied by the Germans. Forced to remain in Norway, he performed only occasionally, but used his time to transcribe and learn classical pieces and to work as a courier for the Norwegian resistance. Those classical pieces were the mainstays of his post-war career.

When he returned to Europe in 1947, the variety show was a thing of the past. Tollefsen made his living doing concerts in Europe, the United States, Iceland, and Africa. He performed as a solo artist and with symphony orchestras. It was during this period that he was recognized as the preeminent accordionist of Europe. When Tollefsen and his wife returned to Norway in 1961, it was for good. He accepted a teaching position in 1963, and his many students include some of the most famous accordionists in Europe. He concludes by talking about and comparing accordions he has played. The book concludes with brief essays by Mogens Ellegaard and Ola Kai Ledang on Tollefsens’s influence on students of the accordion, on changing musical contexts of accordion music, a complete discography by Tom Valle, and a concluding essay on the accordion as a concert instrument by Jon Faukstad.

Several features of this book are particularly striking. Because Tollefsen was an observant, thoughtful man, his career narrative is also a history of popular music and its venues in the early and mid-20th century as seen through the eyes of a major participant. A recurrent theme in this history is adaptability. Before he left Norway for England, Tollefsen was so busy learning new tunes that he had no time to develop skills through scales, arpeggios, and exercises. He integrated technical practice with learning tunes and developed his own techniques. He made his living and his reputation in the 1930s playing in variety shows, which featured brief appearances requiring him to set his performance off from those that preceded and followed his own. Pieces had to be short, familiar to audiences, and highly ornamented—flashy, in a word. Work was scarce during the war, and keeping a low profile meant playing in Sweden and Denmark occasionally, playing for food occasionally, and always avoiding German intelligence. Post war Europe required yet another adaptation. The concert stage required a different repertoire and performance format, two hours plus encores being most common. Flashy technique was replaced by flawless, emotionally engaging renditions of classical genre pieces. The concert stage involved the performer as entrepreneur, and Tollefsen’s success depended on his ability to take calculated financial risks. Teaching involved new adaptations: figuring out how he did what he did in order to show it to students and finding ways to help students play “new music” that he did not particularly like. Finally, Tollefsen’s discovery and involvement in Christian Science is fascinating and moving.

Interviewing is not easy, and using the interview as a presentation format is even more difficult. Not only does Faukstad pull it off, but he does it in as professional a manner as any journalist or social scientist. His questions are meaty, at times pointed; he asks them and then gets out of the way so Tollefsen can talk. Also striking is Owen Murray’s translation from the Norwegian. First, he uses translation to give us access to this narrative, and next, he designs his translation to capture the vibrancy of this man, the flow of the narrative, and the immediacy of it. We feel like eavesdroppers rather than readers.

This is a book equally suitable to fans of accordion music, to those interested in the history of accordion music and accordionists of the 20th century, and to those more generally curious about changing eras of taste in the popular music of Europe and the U. S. during the 20th century.

Kudos to Faukstad, Murray, and ZZ Music for making this work available. It is a gift.

Michael Lieber

University of Illinois, Chicago

ZZ Music wishes to thank Michael Lieber for his much appreciated review.